Mackerel

Our mackerel is Chilean Jack Mackerel (Trachurus Murphyi), harvested off the coast of Chile. This mackerel may be on the smaller side, but they’re a great way to add more omega-3s to your diet: each can contains 750 mg of omega-3s. Also, smaller fish like mackerel don’t have the high levels of toxins often found in larger predator fish like tuna and swordfish, making them safer to eat.

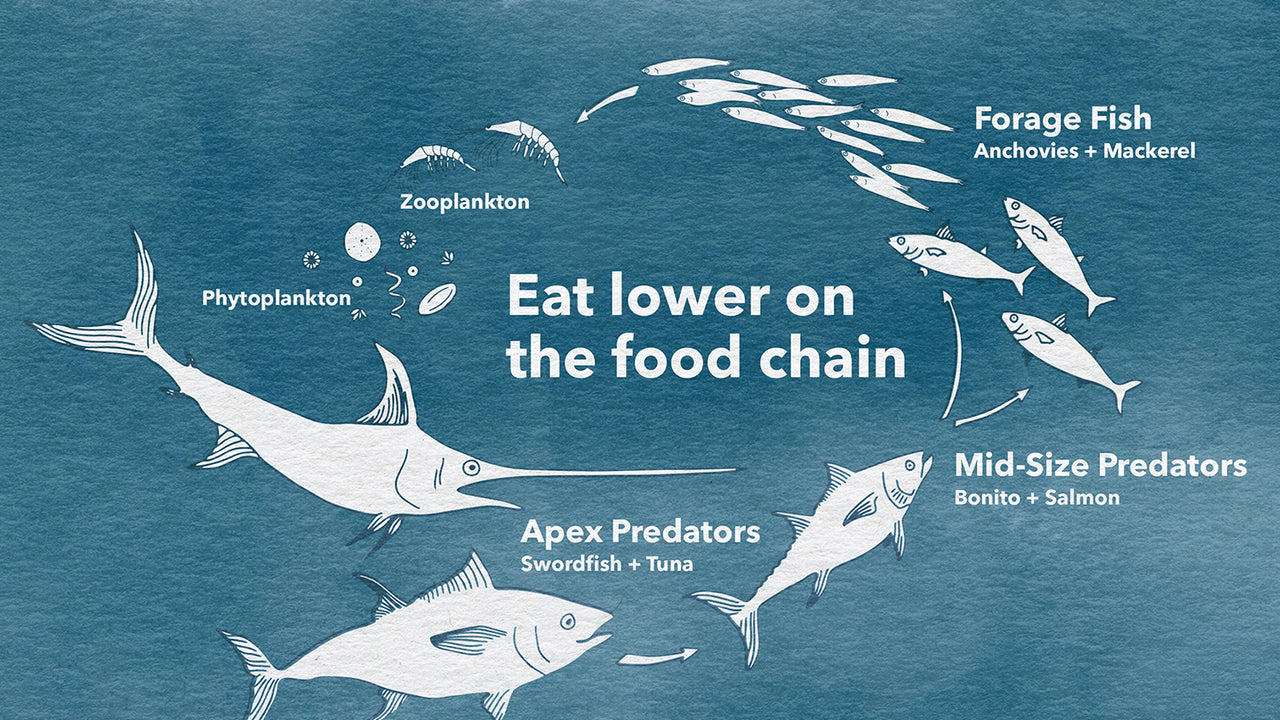

Each can of our jack mackerel contains more than 21g grams of protein (41% to 44% of the daily value) and is an excellent source of vitamin B-12, selenium, vitamin E, and Niacin.* Chilean Jack mackerel are low on the food chain, feeding on small crustaceans and fish larvae, so they don’t accumulate toxins in the way that higher-level apex predators can over the course of their longer lives. Because toxins are passed up the food chain, they become more concentrated as animals eat and then are eaten in turn.

*See nutrition information for total fat, saturated fat and sodium content.

Chilean Jack Mackerel: a story of positive change

Enviro: Small Fish, Big Impact

Eating mackerel takes pressure off larger, overfished species like tuna. This allows the less abundant fish stocks to recover.

“Forage fish—such as mackerel, sardines and anchovies—are low in the food chain,” says Tatiana Lodder, Seafood Assessor for Good Fish Foundation, an organization dedicated to fish conservation. “There’s a lot of biomass and they’re much more resilient than the larger, higher trophic species.” The Good Fish Foundation carefully assesses our mackerel stock to ensure there’s plenty left—for us and for other species that depend on them for food.

Partners: Guided by Science