Bison

Photo: Jill O’Brien

We acknowledge that the bison we source come from ranches built on unceded lands of the Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains, including the Oglala Sioux (Lakota), Santee Sioux, Blackfeet, and Crow. We acknowledge the injustice of their removal from these lands.

Our bison are part of an ambitious effort to restore America’s Great Plains. They roam freely across thousands of acres of open prairie, naturally restoring the grassland ecosystem as they graze

Nutrition: A Better Red Meat

Photo: Jill O’Brien

Unlike most commercially raised bison, our animals are fed and finished exclusively on nutrient-dense wild grasses. They are never given grain or antibiotics.

The prairie provides an ever-changing seasonal buffet of grasses and wildflowers. Bison, which have evolved over millennia on these lands, instinctively seek out the plants their bodies need. In the spring, for instance, they may feed on green needlegrass or Western wheatgrass, while in the summer they might seek out patches of bluestem.

This diet produces a delicious, lean red meat that’s free of antibiotics, pesticides and added hormones. It’s an excellent source of protein, as well as iron and vitamin B-12. Because our bison graze on wild grasses, their meat has less saturated fat and more potassium than meat from grain-fed bison, and significantly less fat and calories than conventional untrimmed grain-fed beef.

Sourcing: Great Plains Reverence

Photo: Jill O’Brien

Our bison come from Wild Idea Buffalo, a South Dakota ranch alliance founded by Dan and Jill O’Brien. Wild Idea Buffalo takes a holistic approach to raising bison, one that prioritizes the health of both the animals and our planet. “Conservation and the protection of prairie biodiversity are our main products,” says Dan O’Brien. “Bison meat is the delicious byproduct that (sometimes) helps pay the bills.”

The O’Briens respect and revere bison as a keystone species, intricately connected to the health of the prairie (Dan O’Brien has written several acclaimed books on the subject, including Wild Idea: Buffalo & Family in a Difficult Land). Wild Idea bison eat nothing but the grass beneath their feet and are never confined to feedlots. They’re given a dignified end, too: the animals are harvested humanely in the field, far from the stress of the slaughterhouse, and are then processed in the field using mobile, USDA-approved equipment. Now run by the O’Briens’ daughter, Jilian, and her husband, Colton, Wild Idea Buffalo partners with like-minded ranches in South Dakota, Nebraska, and Montana, raising bison over some 500,000 acres of open prairie.

Photo: Amy Kumler

Enviro: Reviving the American Prairie

Photo: Jon Levitt

The topsoil of the Great Plains were once among the richest on earth—up to 6 feet deep, versus the norm of 5 to 10 inches—and supported a thriving ecosystem. Unfortunately, they’ve been decimated by 150 years of mismanagement, including overgrazing by cattle and extractive agricultural practices. Bison can help bring these soils back.

When bison roam, they do much more than graze. Native grasses, key to the recovery of the Great Plains, evolved alongside the bison—which act as “prairie farmers.” Here’s how it works: As the herds brush by ripe grasses, the seeds attach to the shaggy bison coats and then drop off, some distance later, into the shallow imprints of bison hooves. The bison provide natural fertilizer, so the seeds have exactly what they need to spread, sprout, and thrive. What’s more, the bison’s light grazing habits ensure healthy plant growth. Wherever the bison roam, the grasslands spring back to life—and so do native birds, reptiles, small mammals, and more.

That’s not all: The grasses effectively draw down carbon and store it in the soil, turning the Great Plains into one of the world's great "carbon sinks" and a powerful weapon in the fight against the climate crisis.

Photo: Jon Levitt

History: A Violent Past

Photo: Buffalo Skulls, Public Domain

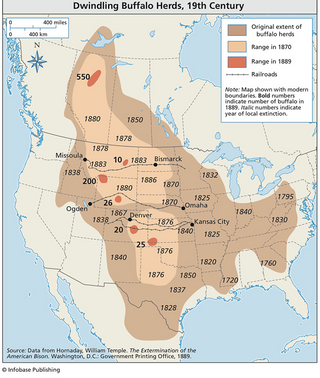

For thousands of years, the Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains—including the Lakota, Arapaho, Assiniboine, Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Comanche, Crow, Gros Ventre, and Kiowa—lived in harmony with bison, relying on the meat for food and the hides for shelter and clothing, taking only what they needed. Everything changed with the arrival of European settlers.

Bison once inhabited almost two-thirds of the North American continent, from what is now Canada down through modern-day Mexico. For the Plains tribes, they were viewed as relatives, part of a shared family of all living creatures, a fundamental source of life and spiritual strength.

In the 1800s, European trappers began shooting bison purely for their skins, killing them by the hundreds of thousands every year. With the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, vast hunting parties poured across the Western plains, slaughtering the animals from the trains for sport. While the American government never made it an official policy to hunt the bison, the army supported this brutal tactic to cut off the Native people’s main source of sustenance. By the end of the century, only a few hundred American bison survived, down from an estimated 30 to 60 million animals in the mid-1800s—and starving Native Americans were driven to reservations.

In recent years, through conservation efforts that include wildlife preserves at Yellowstone and Badlands National Parks, the bison population has rebounded: there’s an estimated 200,000 American bison today—but much more work is needed to repair the cultural and environmental tragedy that remains.

Partners: Guided by Science

Photo: Jon Levitt

One of the most exciting aspects of raising free-roaming bison is their role in restoring native grasslands, thereby combating climate change. In 2015, we partnered with Applied Ecological Services (AES) to study the link between prairie restoration and carbon capture.

A healthy prairie full of native vegetation acts as a “carbon sink,” meaning the plants’ roots draw down and store a significant amount of carbon, preventing it from warming the atmosphere. AES has collected soil and plant samples from various parts of Wild Idea’s prairie in order to measure the amount of carbon held in the soil. Initial findings showed that Wild Idea’s soils had higher carbon levels than conventionally managed ranches nearby. We’ll continue to report on our ongoing studies to see how these soils might affect carbon changes over time.