With The Climate Diet, award-winning food and environmental writer Paul Greenberg offers us the practical, accessible guide we all could use. The book contains fifty achievable steps we can take to live our daily lives in a way that's friendlier to the planet – from what we eat, how we live at home, how we travel, and how we lobby businesses and elected officials to do the right thing. Chock-full of simple yet revelatory guidance, The Climate Diet empowers us to cast aside feelings of helplessness and start making positive changes for the good of our planet. Here we ask Paul for some guidance on how to prioritize the health of the planet in the ways we shop, cook and eat our food.

1. How might switching to a plant-based diet help drastically reduce your carbon footprint?

As I think a lot of us know by now, the two-step process of growing corn and soy, then feeding those high energy foods to animals, and then eating those animals wastes a lot of energy and generates a lot of emissions in the process. Eating plants directly is more energy efficient and thus more carbon efficient. But we should also be a bit careful with our plant-based choices. Highly processed foods that resemble meat take more energy than just simply eating highly nutritious things like legumes and whole grains. Buying hot house grown local produce in the dead of winter is more energy (and carbon) intensive than buying produce that has been grown in a more favorable climate. And eating “flying food,” i.e. air shipped things like fresh berries, can be super carbon-intensive. So, yes, be as plant-based as possible. But be careful.

2. I’ve heard eating certain seafoods can be better for the environment. Which ones are most sustainable?

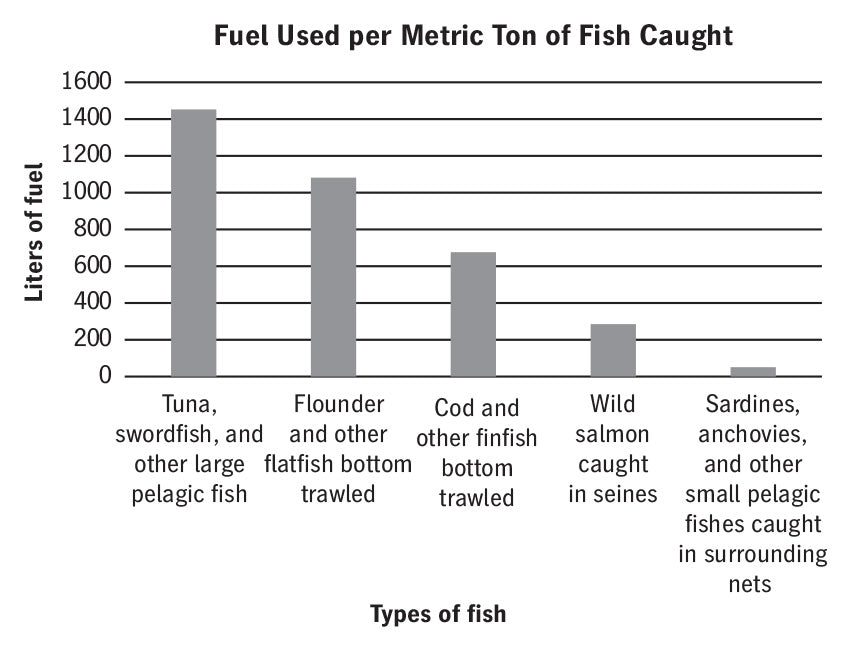

For sure. With wild seafood, any harvesting that drags gear over the bottom is going to be energy intensive. So things like bottom trawled flounder and sole will cost you at the carbon pump. Shrimp, whether farmed or wild, are similarly carbon intensive. But there are some very low carbon seafood options out there. Anchovies and sardines usually caught in purse seines that don’t touch the bottom are super low carbon. Farmed mussels, clams and oysters also pack a lot of nutrition per pound of emissions. Some studies of mussels, for example, put those tasty bivalves at a lower carbon footprint than lentils.

*Robert W. R. Parker and Peter H. Tyedmers, “Fuel Consumption of Global Fishing Fleets: Current Understanding and Knowledge Gaps,” Fish and Fisheries 16, no. 4 (2015): 684–696.

*Robert W. R. Parker and Peter H. Tyedmers, “Fuel Consumption of Global Fishing Fleets: Current Understanding and Knowledge Gaps,” Fish and Fisheries 16, no. 4 (2015): 684–696.3. What are some simple ways we can save energy at home when cooking? What about composting?

Tops on pots is a no brainer. That will cut cooking time in half. Soaking not just beans before you cook, but also pasta is a great thing to do. For example, many recipes for things like lasagna or mac & cheese suggest boiling the pasta before incorporating it into your casserole and baking it. A good soak actually works fine, and saves you the extra cooking energy than advance boiling. In fact, pre-soaking instead of boiling makes, in my opinion, a better al dente mouthfeel. For those who want to be a bit more ambitious, switching to an induction electric stove top is a big energy saver. When you cook on gas, more than 50% of the heat energy from the flame doesn’t actually reach your food. An induction electric stovetop meanwhile conducts around 90% of the heat energy into the pan. And, yes, when you’re all done and cleaning up, don’t forget to compost. The methane from American landfills is an incredibly damaging greenhouse gas, much more potent than CO2, and mostly that methane is coming from food waste.

4. All of these tips can help mitigate the climate crisis, but how can we fight for racial justice while fighting for climate justice?

“The very serious function of racism,” the author Toni Morrison wrote, “is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work.” This is immediately relevant to today’s climate movement. Climate activists speak of this time as an “all hands on deck moment,” with every person needed to transition our society away from fossil fuels. Racism keeps millions of American hands tied and unable to engage in that work. And this is work that is highly relevant to communities of color. As the marine scientist and policy advocate Ayana Elizabeth Johnson quite rightly points out, “People of color disproportionately bear climate impacts, from storms to heat waves to pollution. Fossil-fueled power plants and refineries are disproportionately located in black neighborhoods, leading to poor air quality.” We have to join with those communities and make sure that the low carbon future we all want is fair and equitable across racial and class lines.